The day our lives fell apart, Aug. 15, I received a call from a close friend in Kabul. Usually cool and confident — vital skills for a community leader in a complex, conflict-ridden place like Afghanistan — my friend now whispered in desperation. “I need to get out,” he said. “Help me.” In the background, I could hear the city bustling nervously as millions of people absorbed the fact of the Taliban’s conquest.

My friend, a vocal activist who has spoken out against the Taliban’s oppressive rule, is one of the thousands of Afghans currently fighting to find a way to escape the country. For the past week, I’ve been working from Los Angeles, where I live, to support and coordinate their efforts. Together with a coalition of Afghan American organizations, many community members and I have been trying our hardest to evacuate our friends and family.

It’s fiendishly difficult. A network of veterans, private sector workers, human rights activists and other volunteers, we’re coordinating on different platforms and languages, often all at once. We’re figuring out which Taliban checkpoints to avoid and what gate at the airport is the most accessible, if any are. We’re raising money, millions of dollars overnight, to charter planes. We’re endlessly compiling spreadsheets with information about Afghans who are under threat from the Taliban.

We’re doing this because the American government isn’t. U.S. officials claim they’re presiding over an orderly exit, but the chaos on the ground suggests otherwise. Those evacuated in the past 10 days — approximately 58,700 people, according to American officials — appear to be mostly American citizens and the situation, fluid and frenzied, is far from under control. Friends and family we’ve tried to evacuate have been shot and beaten up by the Taliban, despite American promises of security at the airport. In the absence of guidance, it has fallen to us, using our phones and laptops, to figure out how to rescue Afghans scrambling for their lives.

ADVERTISEMENT

Continue reading the main story

When Afghans speak to me now, they all whisper like my friend, hoping desperately to avoid detection. Their workplaces and homes are being raided by armed men, as the Taliban search for journalists, activists, prominent figures — anyone who has spoken out against their brutality. It goes far beyond critics: In some areas of Kabul, the Taliban are reportedly compiling a list of the houses belonging to members of the Hazara and Shia minority communities, whom they consider heretics. While in front of international TV cameras, the Taliban speak of amnesty for all who fought against them, the reality for Afghans there is completely different.

The people I’m talking to sometimes go silent. All of a sudden, their Twitter and Instagram accounts stop: no posts, no stories, no tweets. Some have switched to encrypted messaging, their communication ever more frantic. For those who venture outside — bravely pouring onto the streets, for example, to celebrate Afghanistan’s Independence Day last week, waving now banned Afghan flags — bullets await. The attempt to flee is perilous. Many, including American citizens, have reached the airport only to be stopped, beaten and turned away. Their homes are now marked by the Taliban.

The Afghan people have been all but abandoned to their fate. Despite its promises to evacuate thousands of at-risk Afghans who assisted the United States, the Biden administration has effectively left the job to Afghan American community organizers, operating from overseas with minimal resources. That must change immediately. The Biden administration needs to establish security in and around the airport, beyond the Aug. 31 deadline for final withdrawal, and make certain that everyone who needs to can make it onto an evacuation flight.

The administration must drop its onerous immigration regulations — for example, asking Afghans to present threat letters and insisting they first travel to a third country before their cases are processed — and provide family reunification applications, which should be expedited and prioritized.

It should go further still. In the aftermath of American intervention in Cuba and Vietnam, refugees from both countries were granted refuge; the same should happen now. The United States has a clear role in causing the humanitarian disaster slowly unfolding in Afghanistan today. For those millions of Afghans whose lives have been turned upside down by two decades of American military action, ending in a poorly organized withdrawal, nothing less than a complete humanitarian parole — offered to any Afghan whose life is in danger — will do.

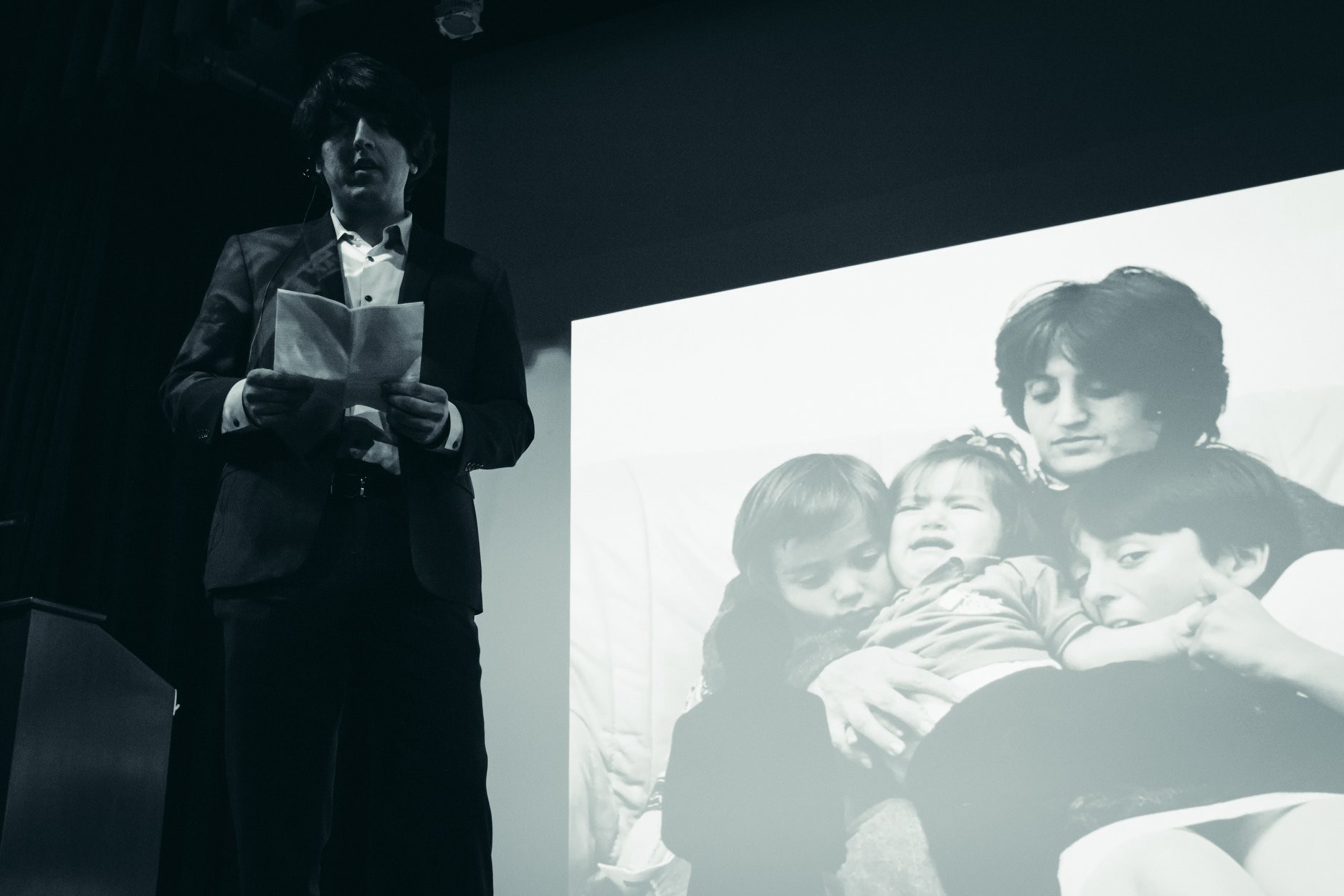

My friend and his family are now in hiding. They live minute to minute, hour to hour, fearing the knock on the door. “I’m so exhausted,” he said when we last spoke, after yet another failed attempt to enter the airport. “I am losing hope.”

His life and countless others are at stake. Mr. Biden must act, before it’s too late.

This was published in the New York Times on August 24th, 2021.